One odd thing I’ve run into in both daytime and astrophotography is the hunt for the perfect image. The number of photographers who mention it, speak about their quest for it, show their edits for it and either feel rewarded or insulted if others don’t share their views has always puzzled me.

The definition of perfect of course takes many forms. Here are a few examples.

Perfection can be the outcome of a contest that assigns a top score. Some would argue that this is the most objective form of perfection. And for many, a score validates what they themselves feel about the creation. But for many, this can also be a source of endless frustration if their creation deviates from the defined rules of creation established by that particular contest. And of course, art is art and some would argue it can never and should never be objectively “scored”. But that is another subject.

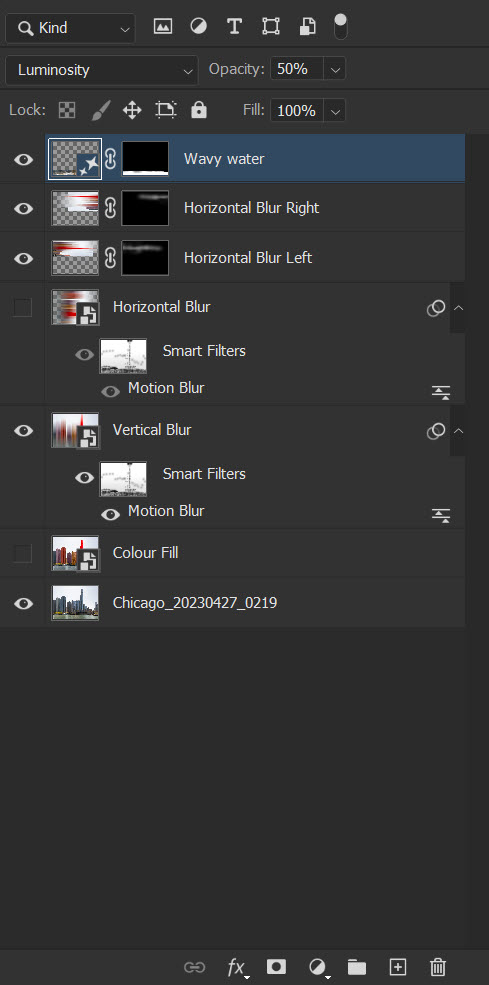

The quest for perfection can also be on display in something like the number of editing layers for a single image in Photoshop – layers that touch every pixel – or at least every area of light and shadow. I’m always impressed by artists who reveal how they created their work and showcase 100’s of Photoshop layers that may touch only a few pixels each time. That they can parse their view of the work into these mini segments is impressive – something I can’t do.

But I must say that as I watch an artist walk through their thought process in Photoshop, I almost invariably find that some decisions they make on one layer, they reverse with another, leaving me again just a bit puzzled overall. But most puzzling to me is how they know when enough is enough. Those decisions always seem somewhat arbitrary to me. Obviously not to them.

Similarly, the quest for perfection can come from the number of separate programs used to make the creation, including programs to clean, arrange, colour balance, remove distractions and clutter, improve dynamic range, separate elements, mask elements, add elements, etc.. Many of these today include artificial intelligence to make the task easier, quicker and more accurate. For both daytime and astrophotography, I have taken courses that invariably suggest a wide range of “necessary” programs to achieve a final result, and I’ve had to learn to be more judicious in my acceptance of their need for my work. Honestly, I’ve found only two or three that really do make a difference for me.

And then there is the topic itself of courses offered. Many claim to offer stunning improvements in imaging results, “professional” quality from “award-winning” artists. I’ve taken perhaps a dozen or more such courses in the last decade, always expecting something magical. What I’ve discovered is that the magic has to come from me – from a vision of what I want the end product or result to be. Sadly, no independent teaching can provide that. You can learn new tools and techniques this way, but those will not get you closer to that elusive perfection.

Sample Deal

Perhaps the biggest contributor to the perfect image is the frame of mind of the photographer who takes it and processes it. I was inspired in August to leap in and process my backlog of astrophotography images because I had had an uplifting experience at a star party, meeting and talking with like-minded hobbyists. I was full of the energy of discovery and really enjoyed the effort to deliver those images. The next batch is waiting for attention – hopefully I can rekindle the feeling.

I recently listened to an episode posted by a photographer who went out with a new lens expecting to make magic happen but discovered that they had forgotten something essential to the day – the camera. A trip back home remedied the situation but left them in the wrong frame of mind to make any meaningful (i.e. perfect) images that day. The episode went on to reveal their dislike of anything they had shot that day. A perfect example of how frame of mind can affect frame of image.

At this stage of my life, there has to be a clear relationship between effort and outcome. And frankly, I’m seeing less and less of that balance in all the hype about the perfect image. There is clearly to me now a point of diminishing returns, and I’ve now found I am able to identify that point pretty much for anything I work on – and frankly, for any decision I need to make in my life.

As an example, one recent lesson in my astrophotography quest was around what to do when the full moon shines its light on the scene. One individual who I do follow did some tests and found that if he used specific filters at specific parts of the night (at moonrise, at moon peak, at moonset), he could “overcome” the effect of the moon and get the “best quality” astro images. This meant programming his imaging sequence with precise timings to switch filters at the appropriate time. Sorry, but no. If the moon is in the line of sight of my intended subject, I will simply not shoot that night. Or I will point my telescope at a portion of the sky without the moon.

And in terms of my life, I feel much more comfortable saying no now to tasks and experiences that don’t have that “perfect” balance of effort and outcome. I’m far less concerned with making others happy or not offending them. I will always decline politely, and say why the answer is no, but will feel no guilt in the decision. Although there are many reasons why getting old sucks, this change in attitude isn’t one of them – I am happy to have made this discovery at this age.

So what is perfection for me in photography? I’ve come to define it as the smile on my face when I see one of my “finished” images in front of me, either on screen or in print. If it makes me smile, it is perfect. Perfection for me tends to be defined by how often I come back to that image, or think about that image. I just want to see it again.

It doesn’t even have to be my image – if I have the same reaction for something I did not produce, I still label it perfect. With my newfound interest in astrophotography, I seek out such images. Two that absolutely fit my definition of perfect are two images produced by the James Webb Space telescope and released fairly early on in its journey of discovery. Can’t stop looking at them. Who could have thought there are such wonders in the sky. Just perfect.